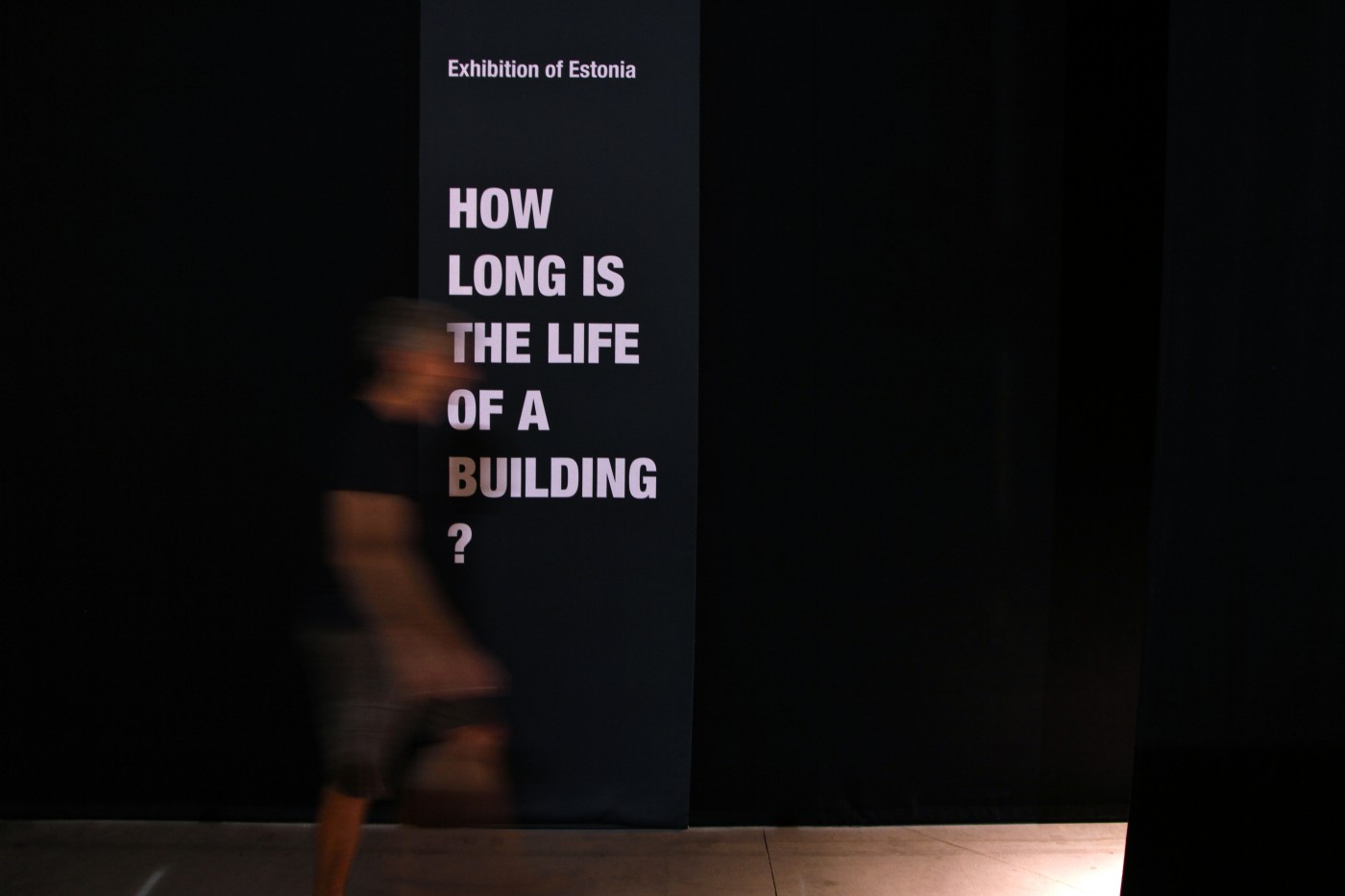

HOW LONG IS THE LIFE OF A BUILDING? – Estonian National Exhibition at the 13th International Architecture Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia 2012

- Ingel Vaikla

- Tüüne-Kristin Vaikla

- Urmo Vaikla

Commissioner Ülar Mark

Assistant Commissioner Regina Raukas

Curator Tüüne-Kristin Vaikla

Exhibitors Urmo Vaikla, Tüüne-Kristin Vaikla, Ingel Vaikla, Maria Pukk, Ivar Lubjak, Veronika Valk

Movies Jaan Tootsen, Urmo Vaikla, Ingel Vaikla

Photos Ingel Vaikla, Urmo Vaikla, workshop participants, archive

Graphic Design Aadam Kaarma

Collaborators Reedik Poopuu, Ann Mirjam Vaikla, Reio Avaste, Heldi Ruiso

Facebook HowLongIsTheLifeOfABuilding?

Catalogue HowLongIsTheLifeOfABuilding?

Estonian National Exhibition at the 13th International Architecture Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia 2012

Everything that is not used goes to rack and ruin. Estonia’s exhibition project at La Biennale di Venezia deals with how the respectable heritage of modernism is fading away, a process fostered by economic and political conditions. Why are distinguished and acclaimed structures that have functioned for only some twenty or so years being abandoned?

Estonia’s exposition is about relating to time and space–to today’s abandonment of important and unimportant places, yet also to alterations and opportunities of tomorrow…posing the question in Venice: how long is the life of a building? This same theme bears more or less universally on architectural heritage throughout the world. Why is modernistic architecture being abandoned – do their materials and technologies depreciate or is it an escape instead, since people have never liked modernist architecture?

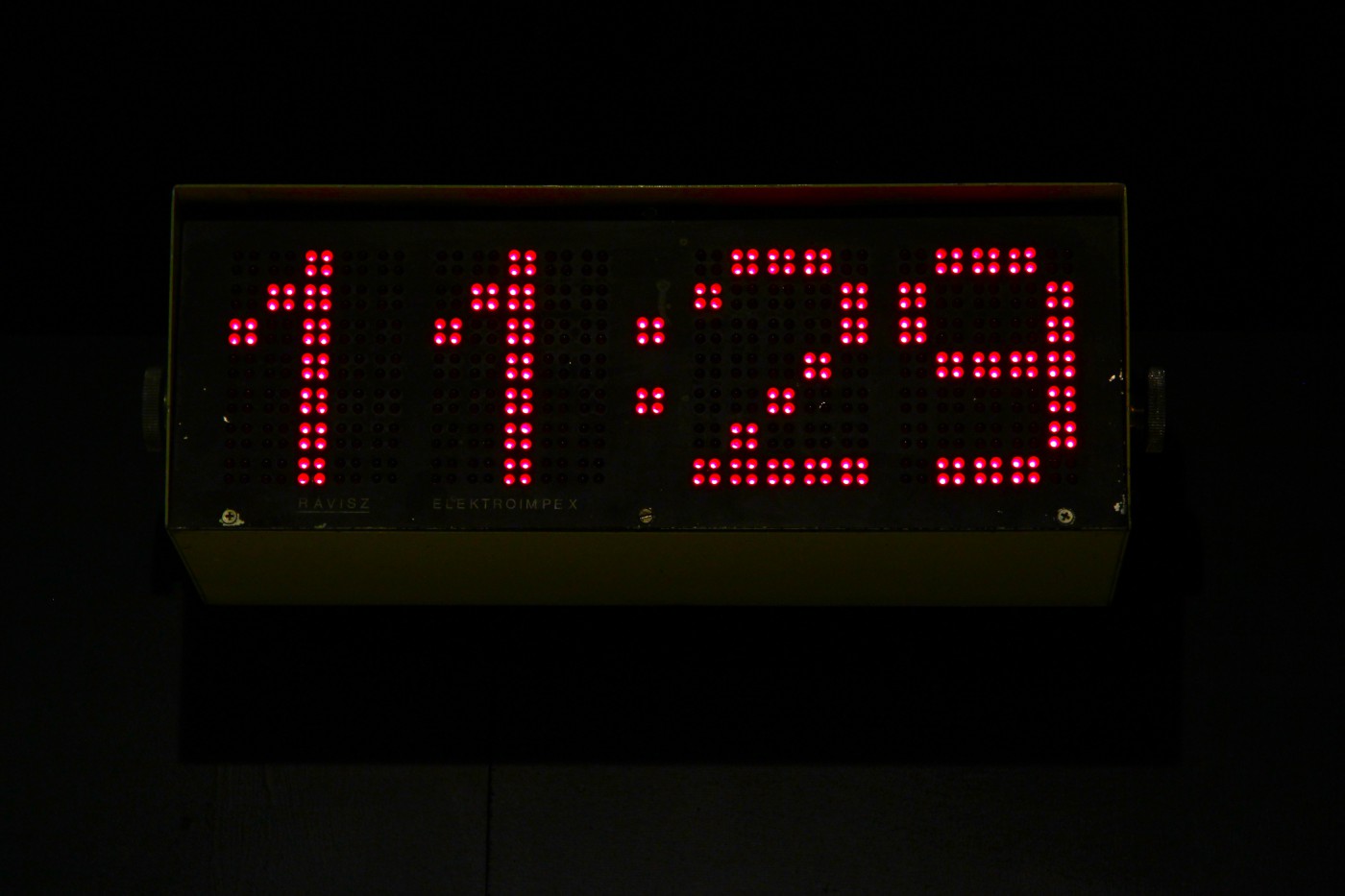

A larger story unfolds through the example of one building, namely the Linnahall Concert Hall. This monumental building, completed for the Tallinn sailing regatta as part of the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games, functioned for only twenty years and stands vacant in the 21st century, covered by now with graffiti. Yet it has aroused the interest of DoCoMoMo. Time stands still in this building, the heating system drones and the clock ticks… This building that stood proudly on a major artery of the capital city is used nowadays only as a training grounds for narcotics dogs and policemen—and for enjoying the sunrise. We have translated the drastic situation described above into a visual poem for the biennial by contrasting the initial official, so to speak monumental range of uses for the building with recent distinctive, spontaneous practices, in order to help viewers recognise and relate to analogous phenomena in their own urban and cultural space.

In the long run, no building lasts forever, yet in today’s world, in the wake of the global economic crisis, we believe it is not particularly sustainable to abandon buildings with quality architecture which have the potential for contemporary alterations. In order to preserve a building, it must change. How can new uses be found for buildings? Reconstruction, in other words adaptable recycling, has demonstrated that old buildings can often satisfy new functions even better than contemporary buildings that are purpose-designed for these functions. The reference point of modernism–form follows function–naturally argues against this. Maybe the great challenge to architects is to move beyond this reference point.